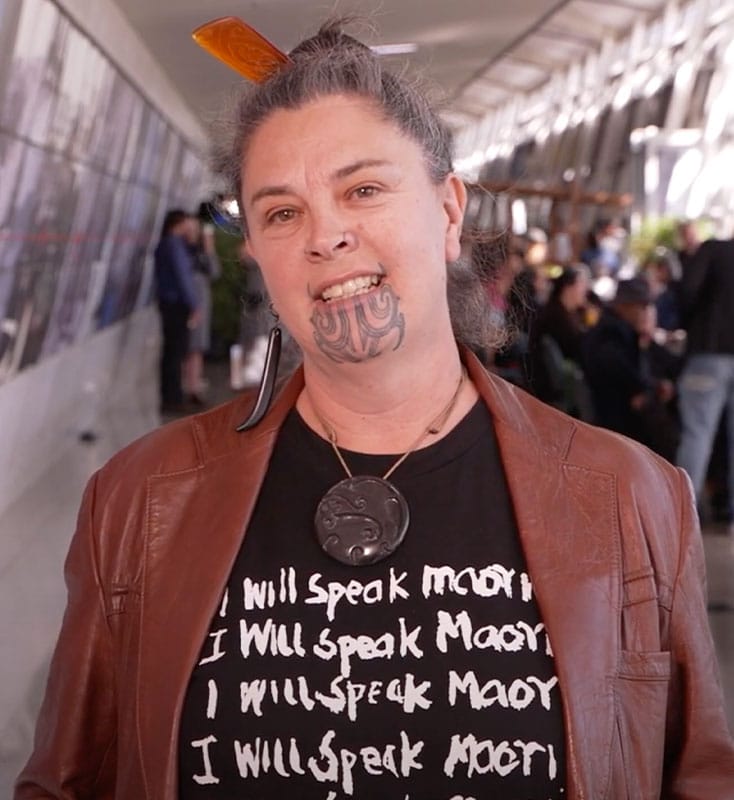

with our knowledge and solutions for better built environments from Te Tiriti based researches.

Whakamana i te tangata Empowering people

With our stronghold of knowledge, we provide he whakataunga/solutions ensuring equitable access to quality housing in thriving, culturally diverse communities to influence change for the ongoing development of housing environments. Here are a few he whakataunga that we have gathered over years of rangahau.

Collection of resources & publications for building homes for small groups or individuals.

Collection of resources & publications that are relevant to the wellbeing of the people, whanau, iwi, etc.

Collection of resources and publications relative to environmental impact and solutions.

Collection of resources and publications relevant to Treaty partnership and helpful resources for policies and government agencies.

Ngā kohinga rangahau Categories

All of our resources can be found under each of these 6 categories.

He rawa mariu Popular resources

List of resources that are sought by most users.